Kéven Breton brings unique perspective to Paralympic sport coverage

“Para athletes are not looking for sympathy, but for respect”

MONTREAL- For Kéven Breton, being a reporter in the mainstream media means more than feeding the professional sports machine.

A visit to his profile page or a listen to his episodes on Ohdio at Radio-Canada provides a rich variety of stories from the sports world including Para sport and the Paralympic Games.

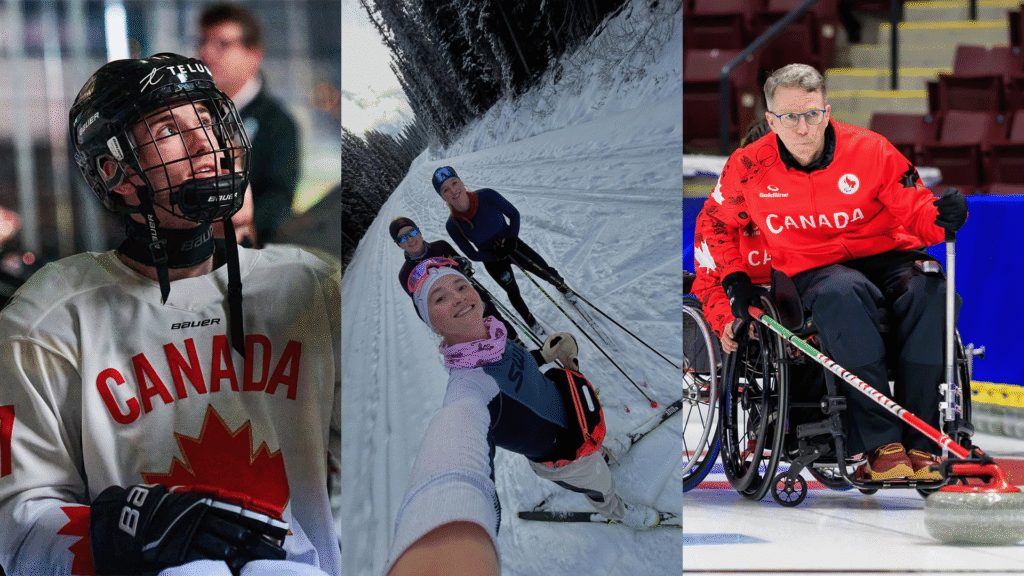

“The Paralympic Games are a window,” said Breton. “They come with their own challenges and perspectives. Winter sport adds another layer — equipment, travel, weather, access. There’s so much happening beneath the surface.”

Breton, who has diastrophic dwarfism, has worked at Radio-Canada as a journalist since 2020. He served as an anchor at the Paris 2024 Paralympic Games and as a commentator for luge, skeleton, and bobsleigh at the Olympic Winter Games.

A native of Saint-Georges-de-Beauce, Breton studied communications in Sherbrooke and originally envisioned a career in radio. As a teenager, he said, covering Olympic or Paralympic competition felt unimaginable.

“I never thought that was something I’d get to do,” he said. “So, every time I’m part of it, I know how fortunate I am.”

With the 2026 Paralympic Winter Games approaching, Breton is preparing for another global sporting stage with real stories that go beyond the medals.

For Breton, covering the Paralympics has never been only about counting podium finishes. It is about performance under pressure — and about athletes who train largely in a low-profile setting.

His path toward Para sport coverage grew naturally from a lifelong love of sport and from personal experience as a person with a disability.

That combination, he said, brought both sensitivity and curiosity — especially toward disciplines and athletes that receive limited attention outside major Games.

“I like covering what people don’t usually see,” he said. “Para sport fits that instinct.”

Breton has worked across professional leagues and international events. But, he said, the contrast is stark when covering Paralympic athletes — particularly in winter sports, where training demands are steep and funding gaps are common.

“Many Paralympians are still essentially amateurs,” he said. “They don’t always have year-round access to physios, therapists, or full support teams. Yet the level of commitment is incredible. That’s what stays with you.”

He said Paralympic athletes are not looking for sympathy, but for respect — and for journalists who approach them with genuine interest in their sport.

“They want to be asked about performance, preparation, tactics,” he said. “Not just their disability. If you’re honest and curious, that’s what matters.”

As attention turns to the 2026 Winter Games, Breton said media coverage still has room to grow — particularly outside the Paralympic window itself.

He would like to see more year-round exposure to Para sports, reducing the need to repeatedly explain classifications and allowing audiences to engage more deeply with the competition.

“The more familiar people are, the better the storytelling becomes,” he said. “That’s true for Paralympic sport and Olympic sport alike.”

Breton will again contribute during the Paralympic Games from Montreal and share roles with reporters on site in Italy. While he would welcome the chance to cover events in person, he said effective coverage remains the priority.

“My role is about making sure the stories get told properly,” he said. “And that they reach people.”

For aspiring journalists with disabilities, Breton’s advice is to stay curious, get practical experience early and don’t define yourself by a single role.

“Try everything,” he said. “Find where you fit. Don’t be afraid to move if you haven’t found it yet.”

As the countdown to the 2026 Games continues, Breton said the mission remains the same: tell the stories that explain why the Paralympic Games matter, whether it’s on ice or mountains.

"*" indicates required fields

"*" indicates required fields